A big, fat short story anthology is the perfect solution when I’m torn between wanting short bites of fiction that I can squeeze in between tasks, and wanting my reading pleasure to never end. My recent favorite has been Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird (2012), a lovingly curated history of Weird fiction from 1907 to the present, which, at 1,126 pages, has lasted me through many cycles of thick and thin. I find the collection eye-opening for two reasons. First, it places people like Kafka and Lovecraft in the context of their less famous influences and contemporaries. This has helped me to finally see which of the characteristics I always associated with the big names were really their original signatures, and which were elements already abroad in the Weird horror but which we associate with the big names because they’re all we usually see. Second, it’s refreshingly broad, with works from many nations, continents, and linguistic and cultural traditions.

But as a lover of Japanese horror, I can’t help but notice how Japan’s contributions to the world of Weird aren’t well represented, and for a very understandable reason. The collection has great stories by Hagiwara Sakutar? and Haruki Murakami, but the country that brought us The Ring also puts more of its literature in graphic novel format than any other nation in the world.

At its peak in the 1990s, 40% of Japan’s printed books and magazines were manga, compared to, for example 5% in Finland in 2009, and 6.1% in comics-saturated France in 2003.* So, a prose collection, no matter how thorough, simply can’t cover the major names that I associate with Japanese horror, like Kazuo Umezu, Junji Ito, and Hideshi Hino.

At its peak in the 1990s, 40% of Japan’s printed books and magazines were manga, compared to, for example 5% in Finland in 2009, and 6.1% in comics-saturated France in 2003.* So, a prose collection, no matter how thorough, simply can’t cover the major names that I associate with Japanese horror, like Kazuo Umezu, Junji Ito, and Hideshi Hino.

*For the 40% statistic for Japan, see Frederik L. Schodt’s Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (1996) pp. 19-20. The number is still often cited, but is now more than fifteen years old, and certainly needs to be updated to reflect changes in manga publishing, including the rise of e-readers, the post-2007 recession, the animanga boom, and the hit taken by the Japanese printing industry after the destruction of ink factories during the 2011 T?hoku earthquake and tsunami. See also “Book Publishing in Finland, 2009,” Market Share Reporter (2012), and “Book Publishing in France, 2003,” Market Share Reporter (2009).

This absence is especially conspicuous to me, as someone who follows the manga world closely, because Japan’s horror manga have a closer tie to the short story format than just about any other manga genre. Most of the manga coming out these days are long, ongoing stories which maintain steadier sales, but Japan still produces a lot more short story manga than we see internationally, since longer, merchandisable series are more likely to be licensed for foreign release. But modern manga grew out of short works—in the first decades after World War II, long stories were far outnumbered by shorter forms. For a long time, the most common kind of manga was the four panel comic gag strip, basically a newspaper comic, though hardly any of these have been translated into other languages (in English see The Four Immigrants Manga, or OL Shinkaron translated as Survival in the Office and excerpted in Bringing Home the Sushi). Also more popular in the past, and seen more often in Japan than in translation, are episodic serial stories (like Black Jack or Oishinbo), and short stories.

Short stories are big in horror manga, more so than in just about any other genre. After all, short stories give the authors liberty to kill or destroy their characters (or the Earth) at the end. Also, while a lot of manga are written hoping or expecting that they could be made into anime (or in the case of romance or slice-of life works, live action TV), in Japan horror stories are more frequently adapted into (often more profitable) live action movies. A short story is a comfortable length for a movie script. This Japanese taste for live action horror is why there are live action versions instead of anime for big-name horror manga like Tomie, Parasyte, and (a particularly unsuccessful attempt at) Uzumaki. Even Death Note was remade as theatrical live action before the animated series, due in part to its horror undertones.

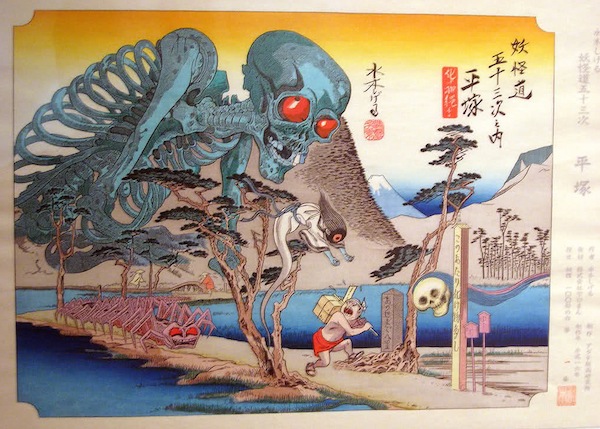

Folklore is another big bond between horror and short stories in Japan. Japan is saturated with ghost stories, made possible largely by the way that Shinto belief invests all objects and places with spirits. The adorable and awe-inspiring nature spirits we’re used to seeing in Miyazaki movies can also be terrifying in the right kind of story, and generated a huge variety of ghost story and demon folktales. Some of these were written down in Kabuki plays or short stories, but a lot of them survived only in the oral tradition, a form which naturally trends toward short-story-length tales which can be told aloud around the fire.

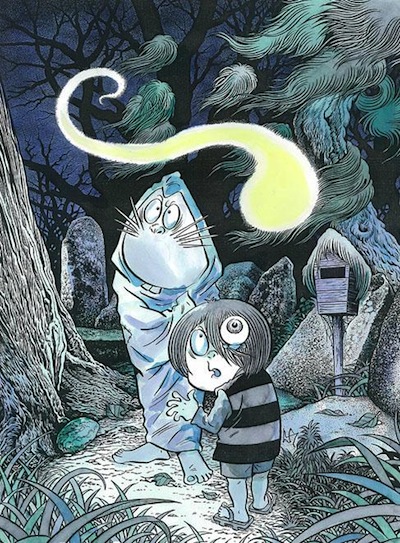

Many of these tales were lost during cultural upheavals in the 2oth century, and a lot more would have been if not for one of their great defenders, manga author Shigeru Mizuki. He set about collecting these ghost stories, which had delighted him ever since he heard them as a little boy. He fought in World War II and even lost his dominant arm, but taught himself to draw all over again and set about recording traditional ghost stories in manga format.

The recent (and long-awaited!) English edition of his best loved work, Kitaro, called itself “quite possibly the single most famous Japanese manga series you’ve never heard of,” and it isn’t kidding, since the adorable little zombie-monster Kitaro is nearly as well known in Japan as Astro Boy. In the manga, Kitaro wanders Japan meeting traditional folklore creatures, many of which had never been described in written form until the manga was produced. The series is thus a treasure-trove of literally endangered ghosts and monsters, which might have been forgotten otherwise. It’s also wholly episodic, basically serial short stories strung together by its morbid and adorable protagonist.

Dozens of other ghost story series and other supernatural horror works imitated Kitaro and its episodic short-story-like structure.

Horror manga for women too—a booming genre, saturated with dashing exorcists and sexy vampires—are usually long-form, which gives romance and characterization time to become more complex. But even these frequently preserve an episodic structure, as we see in series like Bride of Deimos, Pet Shop of Horrors, and Tokyo Babylon.

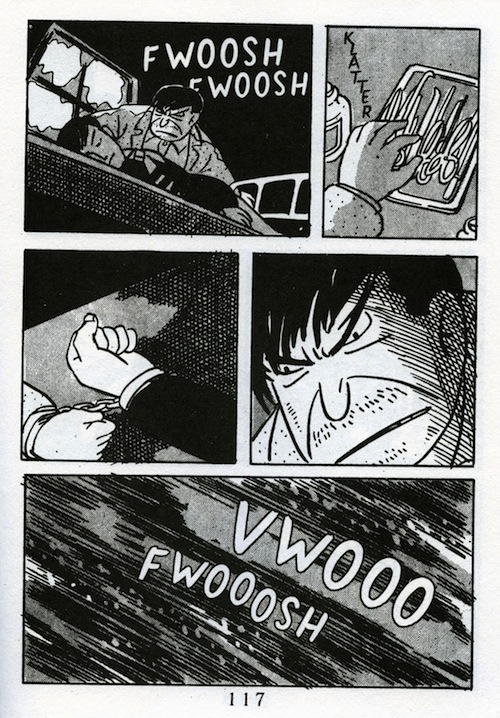

And there’s a third reason why horror shorts have thrived where other manga genres turned away: gekiga. The gekiga movement began in 1957 and was a reaction against how early post-war manga were mostly kids’ stories and light humor. Gekiga authors focused on dark, dramatic, suspenseful stories which developed slowly, using lots of pages of dialog-free atmospheric and action sequences to establish mood and tension. If you’ve ever noticed how manga often take ten pages to establish dramatic mood and action where X-Men would cram the same action into a single page, this movement is a big part of why.

The best description of gekiga available in English is Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s autobiography A Drifting Life, and the best example is probably his infamous crime story Black Blizzard. Because they were trying hard to push the envelope, gekiga often had crime, violence, horror, and unpleasant social undercurrents as their big themes. In fact, the movement was so synonymous with the push against manga being seen as a kid’s genre that for a while the Japanese equivalent of the PTA pushed to ban any manga that didn’t have a certain quota of word balloons per panel.

The heart of the gekiga movement rested largely in short stories. These were originally published in anthology magazines like Garo (1964-2002) and Kage (“Shadow,” founded 1956), but they even have a current descendent in the underground comics anthology Ax (founded 1998, vol. 1 out in English). When other manga genres eventually turned away from shorts and toward long narratives, gekiga continued to produce shorts (see Tatsumi’s short story collections out in English, especially Abandon the Old in Tokyo). Horror stories also largely retained their short form, and continued to make frequent use of the signature gekiga technique of using long sequences with little-to-no dialog to establish mood, suspense, and madness.

The heart of the gekiga movement rested largely in short stories. These were originally published in anthology magazines like Garo (1964-2002) and Kage (“Shadow,” founded 1956), but they even have a current descendent in the underground comics anthology Ax (founded 1998, vol. 1 out in English). When other manga genres eventually turned away from shorts and toward long narratives, gekiga continued to produce shorts (see Tatsumi’s short story collections out in English, especially Abandon the Old in Tokyo). Horror stories also largely retained their short form, and continued to make frequent use of the signature gekiga technique of using long sequences with little-to-no dialog to establish mood, suspense, and madness.

My question becomes: if The Weird had been able to include just one example of a manga, what would I pick? It’s easy to go for something classic or famous, like a chapter of Kitaro, or an excerpt from Kazuo Umezu’s Cat-Eyed Boy. There are also really powerful edgier, adult works—the kind that still make you shiver when you think about them years later—like Hideshi Hino’s A Lullaby From Hell (a condensed version of his unforgettable Panorama of Hell), and the short stories The Life of Momongo and Punctures from the underground manga collection Secret Comics Japan. But for me, lingering creepy memory is not enough. My ultimate test for the power of a short horror manga is very simple: has it made a housemate burst into my room and wave it at me shouting, “Ada! What is this manga? You can’t leave something like this just lying around!” Over my many years of manga reading, three have passed that test. One has passed it no less than four times.

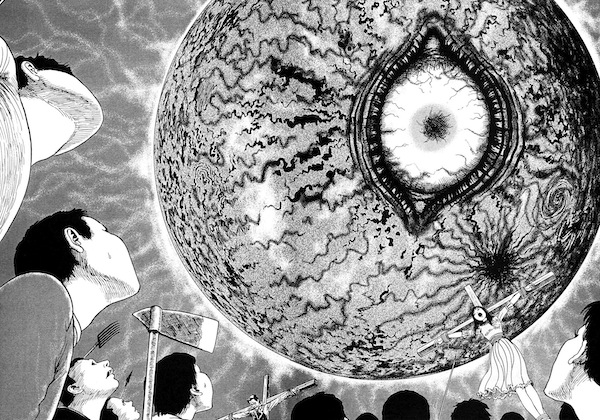

Four times, I’m not kidding, people have burst in to rant about this manga. I’ve had friends say that it was still creeping them out after weeks, even years. It’s The Enigma of Amigara Fault, by Junji Ito. Junji Ito is one of my favorite manga authors because of his ability to develop what seem like campy, even laughable, horror premises into fantastically chilling stories. My favorite of his series, Uzumaki, is about a town cursed by spirals; it may sound lame, but it will genuinely make you feel a little shiver every time you see a slinky.

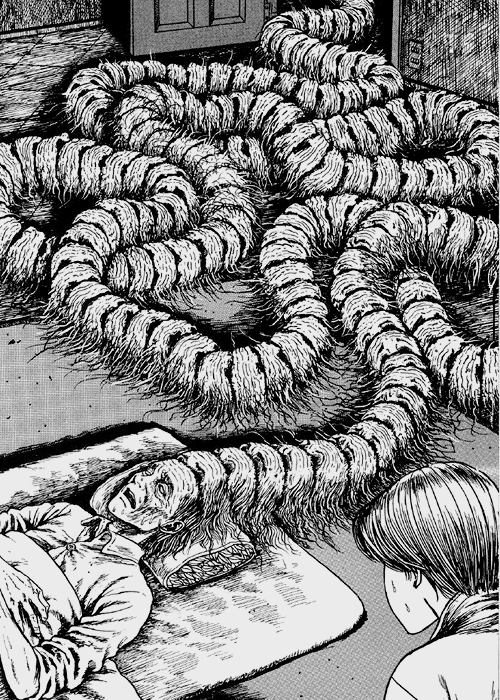

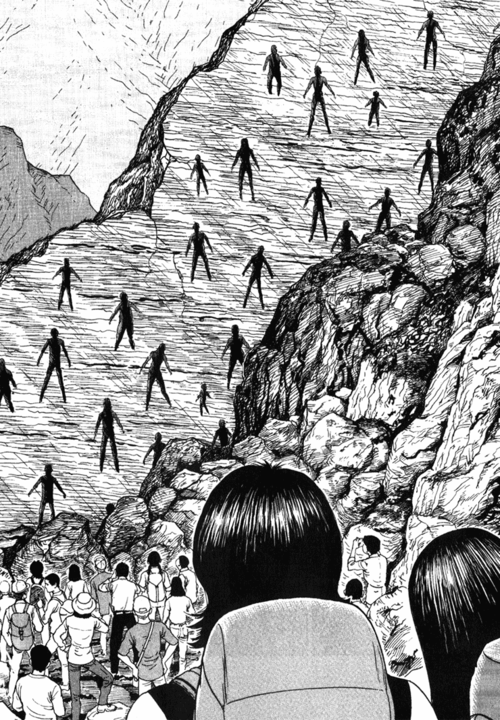

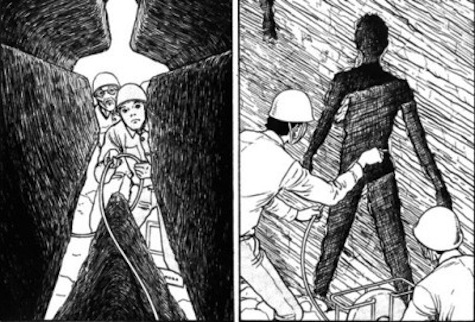

The short story The Enigma of Amigara Fault appears in English in the back of the second volume of his two-volume series Gyo (another great manga, about fish with legs! They’re scarier than they sound, I promise!). The book doesn’t even warn you there’s a short story there, you just get to the end of what you were reading and turn the page wondering, “What’s this?” and innocently start to read. The story about an earthquake which opens up a fault line in a mountain, exposing a bunch of a bunch of weird people-shaped cracks in the ground. Doesn’t sound particularly scary, right? But it’s never possible to summarize why a Weird tale is so powerful, especially a short story, and it’s ten times harder with this kind of manga where two thirds of the answer is: it’s creepy because it looks so creepy! It’s creepy because… because… well, seeing is believing.

The image at the top of this article is from the one-volume Remina, by Junji Ito (not yet published in English, but, like many rare Ito works, it is available in French).

Ada Palmer is an historian, who studies primarily the Renaissance, Italy, and the history of philosophy, heresy and freethought. She also studies manga, anime and Japanese pop culture, and has consulted for numerous anime/manga publishers. She writes the blog ExUrbe.com, and composes SF & Mythology-themed music for the a cappella group Sassafrass. Her first novel is forthcoming from Tor in 2015.

Ctriticising a collection of 30s prose stories for not being a collection of 90s comics seems a little off, TBH, but a big anthology of Ito style stories would certainly be welcome.

Arttt — The Weird isn’t a collection of 30s stories, it’s a collection of stories from across all time and space — well. all time and this whole planet. I think it makes for an interesting comparison.

Thanks so much for the heads up about Kitaro. Going on my wishlist.

My friend introduced me to Gyo and Uzumaki. Ito is the king of weird. I also really enjoyed his ‘Cat Diary’.

Yes, Ito’s ‘Cat Diary’ is one of my favorites too. For those not familiar, it’s a parody of horror manga playing off of how people enjoy telling stories about pet cats being cute. In it Ito depicts himself interacting with his cats, but he draws it like a horror manga, exaggerating the ways in which cats’ crazy behavior can be creepy. It’s hilarious. Sadly, not yet available in English.

Awesome, thanks!

Welcome to the Tor.com party!

Uzamaki sounded really lame to me. Then I read it. I lost it halfway through. Ito is for me a manga version of Lovecraft at his best- he sneaks up on you with atmosphere and innuendo until he hits you with something freakish that leaves you reeling and shaking. I am actually scared to read the story you recommended. But I will anyway.

shellywb — Yes, that was just my experience of Uzumaki too, the amazing way it builds from what seems like a laughably lame start.

Gorgeous Gary — Thanks! It’s great to join!

Oh my God that short story. I really have to stop reading Ito, but he’s so good I can’t. This one will give me nightmares.

I tend to prefer the manga folklore and ghost stories that are a bit tamer, because I’m a total chicken. I love how big and varied the genre there is though, because everyone can find things they like.

Wonderfully written and informative.

As a huge fan of weird and horror fiction/comics/manga, I’m always sad to see the Japanese contribution not fully recognized within the genre. I would LOVE to see a hardcover collection of Ito’s short stories. Even though some of his endings can lack an oomph, overall atmosphere of his stories is just suffocating and dreadful and he has a great ability to build things horrors up.

The re-print of Uzamaki was a surprise and I hope it hints to future re-prints of his stories.

And Mizuki! OH, one of my favorite mangakas! His NonNonBa manga is a testament to his skill as a cartoonist and storyteller. His ability to meld Japanese folklore & childish horror through a slice-of-life filter in which we slowly journey as told through his life; brilliantly executed

Are you a fan of Fuan no Tane? I actually wrote a little short post on it: http://the9thblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/some-rambling-thoughts-on-fuan-no-tane.html

Or a fan of Ogawa’s Revenge? Or Shintaro Kango?

I love this piece, thanks so much! I’m a huge fan of Junji Ito, weird fiction, etc. and wrote a piece for my own blog a while back celebrating Ito’s work. Can I share here? Is that appropriate?

http://nerdoutwithme.wordpress.com/2013/04/18/horror-and-the-surreal-exploring-manga-artist-junji-itos-work/

Cheers!

Logan

Nice overview article. I’ve read most of the manga quoted, and fyi if you can read French then there are a lot of interesting horror manga available. Such as nearly all of Ito’s stories.

Regarding Amigara Fault, yes it is an absolute masterpiece. I also thought that it would have been very apt to include it in The Weird which is indeed a very good and varied genre overview. It is just as powerful as the best prose weird tales. Ito’s manga can be gross, in this case he builds a perfect weird atmosphere.

Regarding Uzumaki, it is indeed one of his better works (most of his more recent longer work cannot reach this level). Towards the end the story builds a perfect Lovecraftian atmosphere of cosmic horror, without an Old One in sight. Remarkable and surreal.

Of his more recent work, Lovesick Dead is very effective. I read it in French (Le Mort Amoureux). The best of his movie adaptations is said to be Long Dream, which I sadly have not yet managed to see.

Regarding the share of comics/manga/etc. among all printed books and magazines in Japan, the figure for 2012 was 36% according to this website that in turn cites data from the Annual Bulletin of Publishing Indicators (Shuppan shihyou nenpou–I’ve been forced to use “ou” for long vowels as the comments function does not recognize my macrons, drat).

http://bizmakoto.jp/makoto/articles/1209/11/news015.html

ohpopshop: Thank you, fresh data is very valuable. I must say I’m surprised how close it is to the number from before. Fascinating.